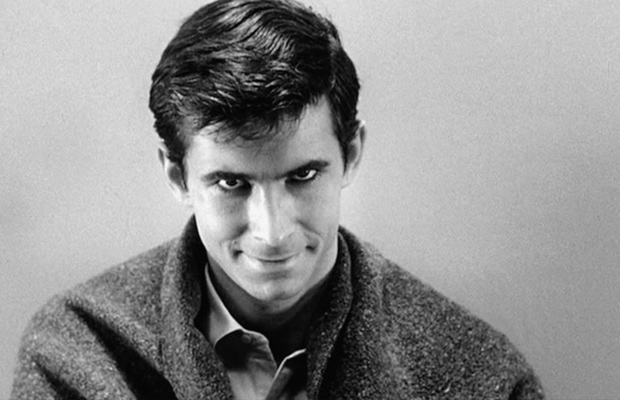

Annual viewings in either my film classes or on my own only solidified my deep infatuation with it. The story of the American Dream, gone horribly wrong, as embodied by an innocent hotel caretaker (the extraordinary Anthony Perkins) and his controlling Mother, remains one of the quintessential tragedies and secular ghost stories.

“Psycho,” which was based on Robert Bloch’s novel and adapted for the screen by Joseph Stefano, was so richly perverse and frightening, the inevitable spin-offs seem to spring more from curiosity than greed. Indeed, whatever happened to Norman Bates, is that hotel still standing and is Mother still around (I’m being vague, in case anyone who has never seen “Psycho” is reading this)?

It stars a game Bud Cort as Norman’s recently sprung-from-the-asylum cellmate who inherits the Bates Motel. A conceptual and tonal disaster, it co-starred Lori Petty, Robert Picardo and Jason Bateman and promised a series that would attempt to juggle horror and whimsical comedy.

I had a videocassette of the pilot, the same way most keepers of The Force own a copy of “The Star Wars Holiday Special” as the go-to example of What Could Go Wrong with your favorite franchise.

The A&E series “Bates Motel,” which (mercifully) is nothing like the 1987 pilot, premiered in 2013 and got off on the right foot from the opening frame. Rather than simply offer praise, let me break down why “Bates Motel” is so remarkable, as both an update of “Psycho” and for being a TV-to-film transplant that truly works.

The Celluloid to Broadcast Conundrum

The formula for transplanting a successful film into a workable TV spinoff has been established, and the results are always inconsistent. In addition to the lower budget constraints of re-hashing a cinematic property, filling in movie stars with television actors has been a death toll for many of these shows.

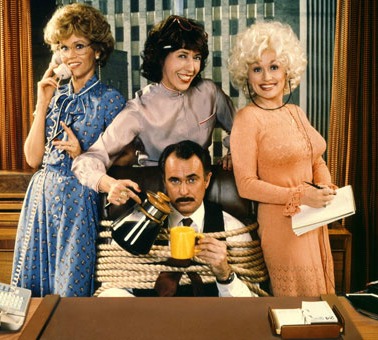

Re-casting the lead role(s) with a new actor is almost always a letdown, as whomever has a lot to live up to, regardless of the film it’s based on. “Uncle Buck” easily lent itself to a sitcom spinoff but unknown stand-up comedian Kevin Meaney was in no way a proper substitute for John Candy, whose soulful comic styling was the heart of that movie. “9 to 5” and “Working Girl” seemed easy fits for television, until someone had to try (and fail) to find replacements for Lily Tomlin, Dolly Parton, Jane Fonda and Melanie Griffith.

Give yourself a hand if you even remember that “Delta House,” the sanitized TV version of “Animal House,” starred Michelle Pfeiffer, or that “Harry and the Hendersons,” with Bruce Davison filling in for John Lithgow, had an astonishing three seasons before fading from anyone’s memory (seriously, does anyone remember that show?).

The alarming number of failed film-to-TV transitions are so great, the question isn’t so much what worked but why bother?

A few of these film to TV attempts came close to working. “Clueless: The Series” lacked Alicia Silverstone and “Honey I Shrunk the Kids: The TV Show” was sans-Rick Moranis, but both shows managed to squeak by for three seasons (!). “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and “Stargate” found enormous success on television by branching out from their established mythologies and expanding from the tone and narrative goals of their cinematic origins.

The same thing happened with the successful “Planet of the Apes,” “Fargo,” “Friday Night Lights,” “Alice,” “Highlander: The Series,” “Fame,” “Weird Science,” “Alien Nation,” “La Femme Nikita: The Series” and “In the Heat of the Night,” all of which overcame their awkward pilots (which played like low-rent remakes of the film they were based) and used their origins as springboards to branch out in different directions.

The animated spin-offs of “Men in Black” and “Teen Wolf” were both better than the original films and their sequels. While there’s no replacing Bill Murray or Michael Keaton, the animated “The Real Ghostbusters” and “Beetlejuice: The Animated Series” nailed the whimsical/creepy comic tone of their respective films and play like solid companion pieces.

In the case of “Bates Motel,” the casting complements “Psycho” but establishes the series as its own entity. Freddie Highmore gets the essence of the character without ever settling for an Anthony Perkins impression. He truly seems to be playing the young variation of Bloch’s character, a monster-to-be with a Pinocchio-like facade.

Vera Farmiga has less to compete with (other than Olivia Hussey’s underappreciated turn in “Psycho IV: The Beginning”) and doesn’t do anything obvious with her characterization. Her Norma Bates is neither crazy nor a sympathetic victim, but walks a fine line in the middle. There are suggestions of incest, both implied and overt, but Farmiga and Highmore, like the show itself, transcend easy sensationalism and find an endearing, if troubling, honesty in their depiction of the story’s central figures.

The story and character arcs created for “Bates Motel” reflect the doomed journey of the Bloch source novel but find ways to flesh out and surprise us. In a brilliant touch, it’s Highmore’s co-star Nestor Carbonell, terrific as the town sheriff, who resembles Perkins the most (a resemblance that will pay off as the character digresses into the mythology established by the film).

The series is inching towards the doomed realities established in “Psycho,” which makes everything feel immediate. Mother’s scatter-brained attempts at maternal control and Norman’s struggle to appear normal are riveting. Rather than root for the characters to embrace their macabre metamorphosis (psychological and physical), not an episode goes by that I don’t hope, perhaps foolishly, that Norma and Norman will ditch the motel, seek decades of counseling and alter the direction they’re taking as motel caretakers.

In Farmiga and Highmore’s hands, Norma and Norman Bates are heartbreaking.

The great ensemble cast is complimented in full by Max Theriot, playing Norman’s brother, and Olivia Cooke, as his love struck best friend. Their characters (and performances) are master strokes in building our sympathies for Norman and his Mother, and finding the heart of this grim love story (Cooke, in particular, is to this series what Janet Leigh was to “Psycho”).

The Belated Companion to “Twin Peaks”

“Bates Motel” is the first television series to effectively tap into the dramatic strength of “Twin Peaks.” I don’t mean it attempts to duplicate the uniquely quirky tone of “Twin Peaks,” which subsequent rip-offs, “Picket Fences” and “Wild Palms,” tried in vain to recycle. Being self-consciously “weird” is not the same as evoking Lynch’s visual expressionism. The power of that series was its distinctly Lynchian theme of the darkness residing beneath the American dream, that anyone and everyone you know harbors a crushing, image-shaping dark secret.

The question it asked, “Who Killed Laura Palmer,” could be answered in a simple, non-spoiler way: Everyone in Twin Peaks, in one way or another, killed Laura Palmer. Either by exploiting or enabling her, or from their indifference, every character on that show, from Shelly the waitress to Sheriff Truman, are indirect culprits and unwilling participants in the murder of the town prom queen.

“Bates Motel” has a similar thematic trajectory. What is Making Norman Bates Crazy? Everyone around him. It’s not just his Mother or his dark background. Life, in the physical form of the colorful denizens of the Twin Peaks-like town the Bates’ inhabit, is pushing Norman Bates over the edge.

In the same way, “Twin Peaks” and “Bates Motel” are thematic companion pieces in which the past and present are fused in a compassionate telling of a home town tragedy unfolding, with no one able to save the lives involved.

Creating a World Both Familiar, Foreign and Freudian

While the characters use cell phones and laptops, the “Bates Motel” sets, interiors and exteriors, are close facsimiles of those from “Psycho.” Rather than coming across like an attempt to recreate an irreplaceable classic (an effort that failed even director Gus Van Sant), “Bates Motel” maintains fidelity to Hitchcock and Bloch but infuses an updated vision that feels organic. Rather than seeming anachronistic, seeing Norman and Norma in the 21st century demonstrates how their tale isn’t limited to the 1960s but still has its perverse hold.

The modern-day approach works, and so does a subplot about how the town surrounding the motel is rife with pot dealers. Surprisingly, this welcome addition of a “Breaking Bad”-like plotline doesn’t hinder or distract from the core mother/son dynamics. In fact, it taps into what made that show so riveting: you want to stop the inevitable tragedy from unfolding and wish the characters were conscious of the doomed trajectory they’re heading towards.

“Bates Motel”, despite its modern-day setting, tonally matches the world of its predecessor.

History shows us how hard it is for television to mirror, even adequately, the feel and setting of the film in which its based. “M*A*S*H*” and “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” got it right and arguably honed in on the strength of the source material with more dexterity than the source films ever could.

Add “Bates Motel” to the short list of television adaptations that honors its source and enhances an already great tale. Just remember, no matter how refreshing, stay away from the shower.

“Bates Motel” airs at 9 p.m. EST Monday nights on A&E.

Superb analysis of a terrific TV series, Barry. I can’t agree with your positive words about the sequels to the Hitchcock masterpiece though, but I do think that what makes the TV series work so well is that it is, as you point out, a curious mix of contemporary (cellphones) and the original era of the film, as embodied by the (hot!) Miss Watson. Yet another reason it’s beautifully done… Thanks for the analysis!