This year should have been the 98th annual county fair that takes place in my state.

While some have never taken an interest in a Hawaiian event that brings in massive crowds, the waft of a cotton candy, noisy rides and a glowing carousal, the fair is always something I eagerly await.

Since the novel coronavirus has forced the cancellation of this and many other events, I’ve decided instead to write about one of my favorite horror films about the carnival experience. While it’s not elegant or even a “classic” in genre circles, Tobe Hooper’s “The Funhouse” is a keeper for a number of reasons.

It begins inside a suburban home, in which a first-person camera POV clearly evokes the opening of John Carpenter’s “Halloween.” We watch through the perspective of a masked killer who grabs a knife and stalks a young girl about to take a shower.

All the while, we get views of a Frankenstein and Dracula poster on a wall, a hall adorned with spooky masks, and other visual nods to the horror genre.

Once our masked killer gets to the shower, we get an obvious nod to the most famous scene in “Psycho,” though here there’s nudity and what is revealed to be a toy knife, the result of a rotten little brother terrorizing his teen sister.

Then, we see a dummy head left on a pillow as a prank – possibly a reference to “Dead of Night” (or more likely, the more recent “Magic”). After that, we see a couple watching “Bride of Frankenstein” on TV.

RELATED: Why Classic Horror Movies Shame Modern Thrillers

Clearly, Hooper is having fun and why shouldn’t he? After all, he directed “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” a film that put him in the horror hall of fame. The extensive genre tributes that stack high in the early scenes of “The Funhouse” are a fitting appetizer.

Hooper’s film is an amalgam of horror genre motifs and expectations.

Elizabeth Berridge stars as Amy, who joins her likable but knuckleheaded friends (Miles Chapin, Cooper Huckabee and Largo Woodruff) on a drive to the carnival down the road. A few ominous signs trouble Amy, as the weathered carneys look at her in a menacing manner.

There’s also a harbinger of doom, in the form of a homeless old woman who tells the teens, “God is watching you.”

A carnival worker dressed in an oversized Frankenstein mask seems friendly enough, though something about him feels off. A dare from one of Amy’s friends that they spend the night in The Funhouse leads them into a lurid discovery of perversion and murder.

The use of a traveling carnival as a threat is a classic genre setting, one that the lavish but failed Disney adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s “Something Wicked This Way Comes” would explore two years later.

“The Funhouse” predates Rob Zombie’s brand of redneck-infused, 70’s-era carnival milieu horror films. At the same time, it extends the deranged family dynamic of poor, untamed and isolated miscreants that was present in “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.”

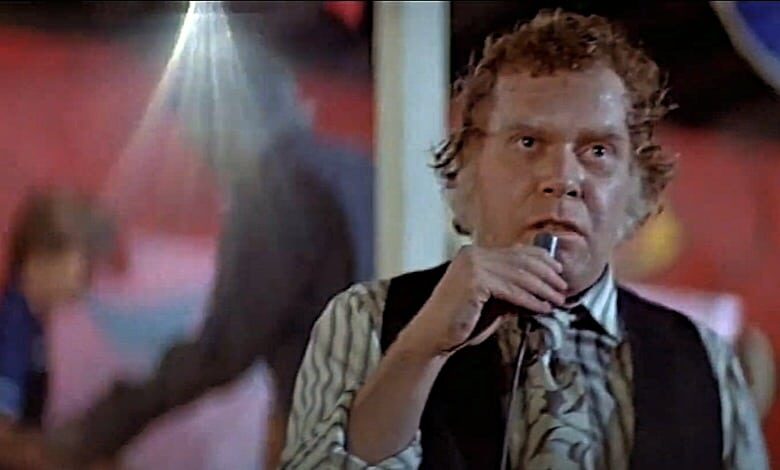

Hooper’s film takes the viewer to each attraction, three of which are overseen by carny barkers (“Step right up!”), all of which are played by Kevin Conway, who gives the film’s most impressive performance. Atmosphere and tension build throughout the first act, in which no one dies (unlike the bloody from start-to-finish initial sequels to “Halloween” and “Friday the 13th” that were released the same year).

Based on an early novel by Dean Koontz, writing as “Owen West,” the book is intriguingly different from the film and offers some rich characterizations. Koontz provided an elaborate backstory for the monster and his carny parents, which is nowhere to be found in the film.

There’s one great shot, where we see a worried mother watch from her bedroom window as her kids drive away to the carnival; it’s among the few nods to the source material. Whereas Koontz’s pulpy thriller includes notes of satanism and rape, only the latter is present in the film and in a suggested, offscreen manner.

This is, to date, the only good Koontz adaptation, with apologies to fans of “Phantoms” (because- okay, everyone now: “Affleck was the bomb in ‘Phantoms’”).

Hooper’s “The Funhouse” arrived a year before Hooper’s much debated directing credit for the Steven Spielberg-produced “Poltergeist.” Working with cinematographer Andrew Laszlo, art director Jose Duarte and composer John Beal, whose contributions are excellent, Hooper shapes one of his strongest films and the first made for a major studio (following his stellar TV movie adaptation of Stephen King’s “Salem’s Lot”).

Despite one of the teens referencing Charles Manson and a few high-rising ’80s hairstyles, the film isn’t dated as much as one would expect. Carnivals, by and large, still look and feel like they do in this movie.

Hooper’s best films (which includes this one) succeed at making the world in which they take place seem vivid, lived-in and authentic. “The Funhouse” conveys the traditional optics and community appeal of carnivals but also visualizes the sinister, outsized threat it can feel like to children.

The carnies on hand are mostly portrayed as alcoholics, frequently seen taking a swig from a flask either before or during a public performance.

The long build up is better than the meandering payoff; a subplot with a boy who runs off to visit the carnival alone is clunky and, despite focus on this storyline, winds up doing little for the film. There are many highlights, however, like a great closing image of a crane shot of silence and emptiness, providing no catharsis.

While Hooper’s film is tonally consistent, it’s the approach to the horror genre itself that is all over the place.

Whereas the opening sequence demonstrates a knowing, pre-“Scream” self-reflexiveness that was ahead of its time, the question is what Hooper was aiming for overall? Is this a teen slasher, an update of the classic Universal Monster Movie, or an extension of the theme of the bastardization of all-American values that marked Hooper’s “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre?”

“The Funhouse” subverts the teen horror movie “rules,” as a character who clearly enjoys sex, hangs out with the “bad” boys, is nude in her first scene and rebellious, lives to the end of the film. However, the other teen characters, who have nothing but sex, weed and mischief on the brain, die terribly.

Amusingly, the four young leads aren’t all that visually dissimilar from the gang you’d find in “The Mystery Mobile.” Had Hooper added a chuckling dog with a jones for “Scooby Snacks,” he could have given us the first R-rated “Scooby Doo” movie.

A few years ago, my wife and I walked through the “Freak Show” at the Colorado State Fair in Pueblo. It featured a two-headed cow and “alien” babies in jars, exactly like the ones you see in Hooper’s film.

At the Old Town amusement park in Kissimmee, Florida, there’s a coin operated attraction where, upon depositing a dollar’s worth of quarters, you watch a mannequin squirm violently in a faux electric chair execution. It’s ghastly to watch but has been there for so long, it has become a noted “attraction” for longtime attendees of the park.

A sharp quality of Hooper’s film is that it reminds us that carnivals are such a natural, expected part of American life, we rarely stop to consider how secure the patron really is while in that environment.

Even in pre-covid-19 times, did we ever go to a carnival wondering how safe those rides are, if the food was up to code and just who the heck are the traveling workers who are running the whole thing? “The Funhouse” takes this fear as far as it can go, by reminding us that, while we’re familiar with how horror movies work, sometimes the monsters we fear the most are real.