Why the Stoned Detective Suits Our Troubled Times

The full quote is illuminating:

“My mind,” he said, “rebels at stagnation. Give me problems, give me work, give me the most abstruse cryptogram or the most intricate analysis, and I am in my own proper atmosphere. I can dispense then with artificial stimulants. But I abhor the dull routine of existence. I crave for mental exaltation. That is why I have chosen my own particular profession, or rather created it, for I am the only one in the world.”

We’re used to seeing our hard-boiled detectives downing bourbon. So it’s hard to think about these characters with any other mind-altering substances.

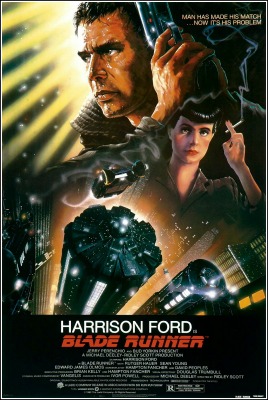

Possibly one of the most iconic shots in film detective history is when Decker (“Blade Runner,” 1982) picks up a shot glass of whiskey and takes a sip.

As the camera pulls away we see a bright red swirl of blood as the glass is slowly set down.

Detectives traditionally have been hard drinking because they face overwhelming odds and the darkest human realities. That makes it fascinating to see a new type of detective with a penchant for something other than alcohol.

Enter the Stoned Detective.

Pick Your Poison

Is there something about cannabis that’s a better fit for the post-postmodern detective than alcohol? I think there is.

It’s all about character development. The hard-drinking detective was honest but an outsider, hardened but not jaded, mission driven but committed to community and family first. Last but not least he was tough.

In the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s the detective was the ultimate outsider who sat between the corrupted powers in charge and the lowly victims below. You have Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade, Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlow, and my personal favorite, Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer.

These straight shooting characters led up to director Roman Polanski’s “Chinatown.”

There’s not a single film student who earns a sheepskin without learning the genius of this film. It’s warranted, of course. Jack Nicholson’s Jake is a little bit of all the past detectives with a mystery that delves deep into the abyss.

But then something shifts: Vietnam and the Baby Boomers, Nixon and Reagan’s ’80s. The hard-boiled detective suddenly seems quaint. What was once a character trait now seems cliched.

Not Your Typical Private Eye

Sure, Decker, drank whiskey and had a gun, but that gun was a blaster and he was chasing replicants. The detective story now had to be set in the future to gain any traction with an audience.

Don’t get me wrong, I love Walter Mosely, and the “Devil in a Blue Dress” is one of my favorite films, but that was retroactive. Like the amazing “LA Confidential,” another film set in an earlier time. The “new” detectives existed either in the past or some far away future.

Surely there is corruption to uncover and mysteries to solve in contemporary times?

The Western cowboy has followed a similar route as the detective. The archetype began in the past, moved to the future, and eventually came back to present times.

“The Road” (2009) reinvents the Western. Now, it’s a post-apocalyptic landscape versus the Western high mountain desert. The themes are still consistent:

- A small but important battle between good and evil

- Guns serve as the mediators of that relationship

- Horses (now shopping carts) are crucial to survival

- Crossing a barren environment with dangerous natives (cannibals), all the while holding onto core values (the child).

“The Road” truly was a Western from an author well versed in the genre, Cormac McCarthy.

The Dude Abides

I bring up the Western because Joel and Ethan Coen make a point of it by having the narrator of “The Big Lebowski” be “The Stranger,” an old Western cowboy played by Sam Elliot. It’s the irony of the movie that,“The Dude” is the right person for the job at hand. His total reluctance and accidental nature of his sleuthing actually works for him.

“The Big Lebowski” hits in 1998, and suddenly we have a new kind of detective. He’s better equipped to deal with the kind of incestuous corruption that permeates our world today. He smokes pot versus drinking whiskey (well, White Russians). He wields a bong, not a revolver, and drives a beat-up car versus a Model T.

Yet the Dude asks the same penetrating questions that eventually uncovers the depth of corruption.

Enter the Stoned Detective

That’s the genius of the stoned detective. It’s not that they’re blithely unaware of what’s going down. They’re very aware but have no illusion that their solving the case is going to make a damn bit of difference.

They’re ten steps ahead of Sherlock, as they’ve solved the case, and the subsequent one. Like a zen monk, they understand nothing has changed. They just want off the wheel of Saṃsāra altogether.

They fight injustice not so much by exposing the “bad men and women’s” deep dark secrets to the light of day, but rather by attempting to shift the conversation altogether. It’s crime solving without the moral outrage.

In “Chinatown” Jake slowly works his way to the top to find the source of the corruption. The stoned detective is more holistic. He has a sense that “as above, so below!” and “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss!”

He’s first going to fix what’s broken within or at least make peace with it.

In the vastly underrated “Inherent Vice” (still believe Joaquin Phoenix deserves an Oscar nom for this role) you have Fascism battling Communism as the backdrop. Our lovable doper detective Larry “Doc” Sportello navigates treacherous waters of solving a missing person’s case. He’s high, everyone’s high, but it keeps him calmly neutral and nonjudgmental.

In the brilliant HBO show, “Bored to Death” which ran for three seasons (2009-2011) you have Jason Schwartzman, Zach Galifiankis, and Ted Danson (who’s so good in this it’s criminal it didn’t get another season) as three misfit detectives who are high all the time. The biggest mystery of all is who’s Jonathan Ames’ (Schwartzman) father and where does his missing sense of adulthood stem from versus uncovering the illuminati or any grand conspiracy.

“Pineapple Express” rounds out the stoned detective genre. Once more, the focus is on my smaller concerns.

If Sam Spade, Philip Marlow, and Mike Hammer had only gotten high, maybe they’d have realized that the real mystery to be solved involved their own hubris and participation in the whole scheme of things to begin with.

Maybe the stoned detective knows something important that we should all pay attention to, “What you focus on expands for you.”

Which explains why the rug is so important after all.

It tied the room, and reality, together man.

Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye did a great job of putting Phillip Marlowe into the milieu of ’70s Los Angeles. What made the film great was that it didn’t try to resolve the anachronism of having a hard-bitten noir detective in the Flower Power era, it underlined it. The anachronism was the point of the story. Elliott Gould’s Marlowe was a conservative man of honor, who wore a black suit while surrounded by scumbags and hippie chicks in bikinis who were completely off his wavelength. That’s what made him so interesting: by standing out like a sore thumb, he embodied the values that had been lost in post-Vietnam America.

Brick was also a really good innovative telling of the detective story.

Brick was awesome. I’m really interested to see what the director, Rian Johnson, will do with Star Wars Episode 8.