David Mamet’s “The Spanish Prisoner” (1998) is the playwright-turned-filmmaker’s most enticing cinematic work.

The theme is the disadvantage of being a nice guy in a world of opportunists who are all too happy to take advantage of someone who is intelligent, kind and naïve. The protagonist is literally a Boy Scout.

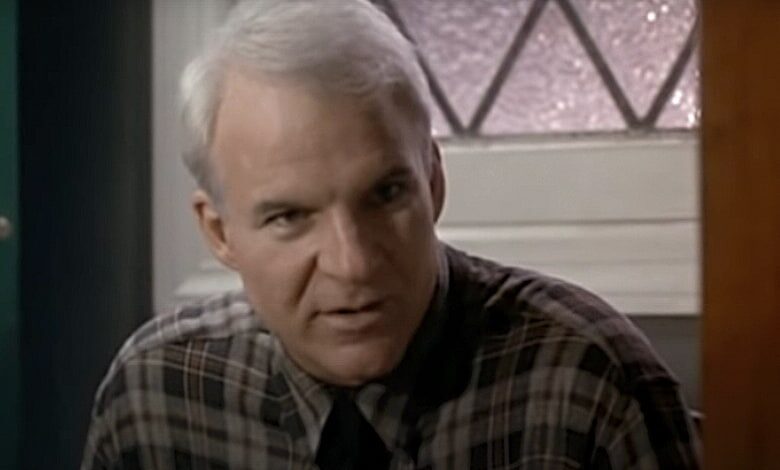

Tonight: THE SPANISH PRISONER, my favorite Mamet-directed film, featuring an Oscar-worthy performance by @SteveMartinToGo pic.twitter.com/4GrH4qfsrX

— H. Perry Horton (@hperryhorton) May 4, 2017

We meet Joe Ross (Campbell Scott), who invents a money-making algorithm/business practice called The Process, which his firm has sent him to the Caribbean to sell. In addition to feeling unease in his own skin (Joe is nice but awkward), he immediately feels the squeeze his work is putting on him over The Process – questions of inter-office trust, nondisclosure forms and which colleagues he can confide in spoil his initial excitement over the project.

A nice touch?

When Joe writes the amount of money on a chalkboard The Process is projected to provide, we don’t see the amount, only the look on the faces of the businessmen.

This is smart direction, as the camera follows all the details we should be following.

Our everyman wants financial success but has principles – while on the Caribbean trip, Joe has his first encounter with Jimmy Dell (a wonderful, wildly against type Steve Martin). Dell offers $1,000.00 for Joe’s camera, which Joe turns around as a “favor” and just hands over to him.

From there, an unusual, somewhat brotherly back and forth builds between the very different men. Jimmy’s initially prickly demeanor becomes a kind of mentorship, as Joe is all too happy to learn how to carry himself in the presence of the rich and powerful.

If The Process is to be Joe’s legacy, then Jimmy is just the person to introduce him into an environment of privilege and cutthroat business maneuvers.

FAST FACT: David Mamet worked at a number of jobs before embracing the arts, including taxi driver, waiter, real estate salesman and a short stint in the Merchant Marines.

So fully immersed in neo-film noir, Mamet’s film could easily have been in black and white. This is more Kafka than Hitchcock, a portrait of justified paranoia. The use of shadows, tight framing on the principals during telling moments and dialogue that knowingly explores thriller tropes (“Who in this world is what they seem?”) suggest a self-knowing exploration of the concept.

The contrast of “You rich people” with a self-described “working man” comes across the strongest between the delicious scenes between Scott and Martin. Mamet may have envisioned a stage-bound design at the heart of his narrative, but he shapes the scenes in imaginative ways (the contrast between Dell’s spa room at night and the same location at day is cleverly depicted).

The ultimate design of Mamet’s narrative is intricate – and so much fun – that you might even forget that you’re watching a thriller for the first hour.

As a playwright-turned-director, there is an inevitable staginess to many of Mamet’s films, though he gradually found the creative means of “opening up” his film works and finding confidence and visual acumen as a filmmaker.

Following his moody, winning 1987 debut “House of Games” (also about the art of the con), Mamet’s subsequent “Things Change” (1988), “Homicide” (1991) and “Oleanna” (1994) were all worthwhile explorations of men playing the roles presented to them in society and finding their weaknesses preyed upon.

After “The Spanish Prisoner,” Mamet wrote and directed the noteworthy period drama, “The Winslow Boy” (1999), and two standout thrillers for the ill-fated Franchise Pictures – “Heist” (2001) and the excellent “Spartan” (2004). Mamet’s last written and directed film to date is the exceptional Chiwetel Ejiofor vehicle “Redbelt” (2008).

As a screenwriter, perhaps Mamet’s track record is even more impressive, having written “The Verdict” (1982), “The Untouchables” (1987), “Glengarry Glen Ross” (1992), “Hoffa” (1992), “Wag the Dog” (1997) and “Ronin” (1998), to name a few.

While Mamet’s origins as a gifted mimic of human speech (his scripts famously have long pauses, stumbled words and an ellipsis to evoke casual, authentic dialogue, requiring some actors to use a metronome to rehearse the cadence properly) are among his defining qualities as an artist, his work as a film director remains under-appreciated.

Unlike, say, Neil Labute, Mamet’s filmography doesn’t have an equivalent of “The Wicker Man” (2006) undermining the best work. Mamet never found outright commercial success like playwright-turned-helmer Sam Mendes.

Although perceived as a small sleeper upon its release in 1998, “The Spanish Prisoner” has an ease, a cool rhythm to Mamet’s reliably stylish wordplay and sleight of hand skill in its storytelling that marks the best of his creative output.

David Fincher’s flashier, far darker “The Game” (1997) was released only months earlier and has a similar “the world against one man” concept (both are like Alfred Hitchcock’s 1959 “North by Northwest” with all the dread and none of the big set pieces).

While less visceral and intense than Mamet’s film, “The Spanish Prisoner” is still better.

Scott is perfectly cast as the audience surrogate, though Joe is guarded and kind of snobbish enough to fall a little short as an Everyman we can always root for. Pidgeon’s performance has a theatrical quality from the very beginning, which winds up a fitting touch for the character. She has a way with odd phrases, like “Shows to Go You” and “Dog My Cats.”

Legendary illusionist Ricky Jay gives a cheeky supporting turn as Joe’s business colleague and Ben Gazzara brings an appropriate level of mystery as someone is either on Joe’s side or constantly undermining him in the shadows.

The best and most surprising turn naturally comes from Martin, who, before or since, has never given a film performance like this. Playing a man exuding elegance but emotional distance, Martin gives his character that perfect blend of someone you can’t take your eyes from, even as we can’t quite find a true entry into his private life.

It’s an excellent turn, as much a hidden jewel in Martin’s body of work as the film is in Mamet’s filmography.

A reference is made about competing at the business level with the Japanese. Later, someone notes the Caribbean as a popular location for Japanese tourists. It leads to a jokey final reveal during the climax that comes across as awkwardly dated and inappropriately jokey, the one touch in the film I hated. Better is the use of “Budge on Tennis” and how a valuable totem (in this case, an antique book) can be used as a passport to a different social class.

There’s also the moment in which Jimmy casually creates a Swiss bank account for Joe, a “lavish awkward gesture,” a scene that is perfectly written, directed and performed.

While the profane grit of “Glengarry Glen Ross” and the anguish of “American Buffalo” are, perhaps, the go-to examples of Mamet’s brilliance on film, his output as a director is full of little treasures like “The Spanish Prisoner” and in need of rediscovery.

This is my favorite Mamet film, and it only gets better with repeated viewings. The characters are so sharply written, the dialogue so clever and the plot is so engrossing. Most scripts would have made Scott’s character at risk of becoming a greedy shark, but he’s the rare ambitious social climber in a movie that is a nice guy and sticks to his principles. That’s something we rarely see on screen. The danger isn’t that he’ll be corrupted but that the cynical world will swallow him up.