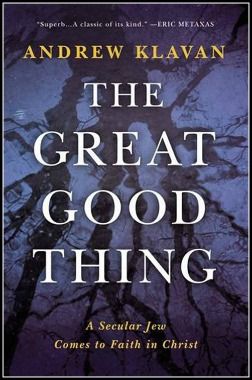

Klavan’s “The Great Good Thing” ostensibly charts the author’s embrace of a religion that clashed with his familial roots.

As with previous Klavan books, that only scratches the thematic surface.

“The Great Good Thing: A Secular Jew Comes to Faith in Christ” is a love letter to the author’s bride and a tone poem to the glories of western literature.

The unlikely memoir doesn’t require a similar sense of faith to cheer. Anyone smitten by crisp turns of phrase will tear through it like one of Klavan’s signature thrillers.

The spiritually inclined, though, will find it nourishing from start to finish.

The author of “True Crime” and “Don’t Say a Word” begins with his 49-year-old self standing outside of a church. His baptism awaits … but how did he get here? Why would a successful, middle-aged man cast aside his Jewish roots in such a public manner?

What follows is a memoir that doesn’t follow the anticipated beats. Yes, we learn about Klavan’s parents. Dad was a radio innovator with a nasty streak. Mom lacked the maternal warmth we read about in worn, hand-me-down novels.

Paging Norman Rockwell

The Great Neck, N.Y. clan had all the trappings of success. They were an upper middle class family anchored by a local radio star. Something profound was missing. To Klavan, that didn’t necessarily mean faith. The family’s Jewish roots were an act, performance art writ large.

The parents were shaped by the culture’s quiet anti-Semitism, a subject given great care and insight. It’s just one way “A Great Good Thing” is far more than a boilerplate transformation yarn.

Appearances meant everything to the Klavans. To outsiders, they provided a portrait of family bliss. Anyone willing to peer deeper into their household would see something bordering on neglect, if not outright abuse.

Klavan’s school days were filled with fantastic dreams, the kind that adhered to the rigorous logic that later fed his fiction career. Back then, the daydreams kept him whole. Sane, even.

Put Up Your Dukes

The young Klavan spoke with his fists early and often. The author describes getting manhandled by a much larger kid during a football game. It’s a memory that speaks of his early mindset, one so hardened it seems like it would be impossible to crack, let alone soften.

He wasn’t dumb but never applied himself at school. He worked the hardest at tricking teachers that he had absorbed the assigned material.

When he later rebelled it seemed like nothing could save him.

And yet slowly, over the years and through a series of revelations he simply couldn’t ignore, Christianity beckoned.

Slowly, we learn how he overcame his objections. Therapy helped. So did meeting the right woman, which began with a “meet cute” moment for the ages.

God and Art

What’s miraculous about Klavan’s transformation is the role western art played in it. He writes of discovering figures like Philip Marlowe in “The Big Sleep,” fascinating souls who reflected Christianity’s impact on the arts.

They drank. They fought. And, ultimately, their moral compasses always pointed north. That spoke to the author, as much as the personal revelations and other signposts that led him on his faith journey.

It’s also where Klavan’s admirers will see the seeds of his fiction career. The flawed heroes who stumble while saving the day.

FAST FACT: Andrew Klavan worked as a radio reporter earlier in his career. One of his more prominent stories involved covering the kidnapping of Patty Hearst.

Klavan didn’t go willingly into Christ’s arms. He examined his own feelings on faith, worrying he was embracing it for all the wrong reasons. It might sound off-putting to read about one man’s rigorous self examination. Klavan makes the process both transparent and fascinating.

“The Great Good Thing: A Secular Jew Comes to Faith in Christ” does more than let a popular crime novelist reveal his darkest hours. It shows how the arts don’t just shape our lives. They speak to our very souls.

Photo credit: KristinaDragana via Foter.com / CC BY