French economist Thomas Piketty is no communist, but he’s no rock-ribbed capitalist, either.

He’s a redistributionist, concerned with the concentration of wealth and the social pathologies that it engenders. His work of a few years ago, “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” is the subject of a documentary of the same name directed by Justin Pemberton, adapted by writer-producer Matthew Metcalfe.

I’ve read quite a bit about Piketty’s book, though not the book itself, so I can’t say whether or not the adaptation is fair to it. It’s clearly not fair to the history it covers, the economics it advances or the societal unpleasantness it proposes to cure.

By relentlessly putting its thumb on the scale, “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” shortchanges Piketty’s legitimate questions about capital, and discredits the solutions he proposes.

Pemberton and Metcalfe lay out Piketty’s thesis in the opening minutes: the collapse of Communism led the pendulum to swing too far in favor of capitalism. In Piketty’s opinion, the “infinite faith” in the deregulation of markets and glorification of private property has led to pre-WWI levels of inequality, nationalism, and xenophobia.

We risk “returning to a capitalist system like that of the 18th and 19th Centuries,” where a permanently wealthy upper class controls the political levers of power, and demagogues distract the masses by manipulating them to hate their neighbors, especially the foreign ones.

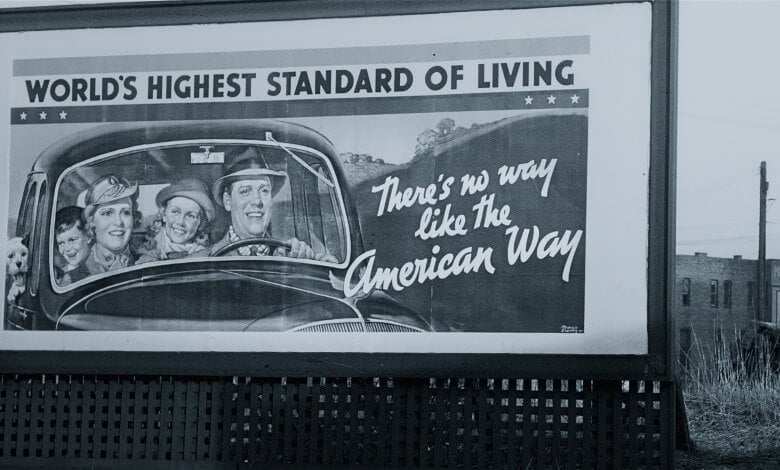

The next hour-plus takes us on an extended, anachronistic and largely fictional tour of the economic history of the west. The visuals are compelling, the storyline coherent, and the experts plausible. Still, the history presented here, while usually not factually wrong, is so over-simplified that it crosses from interpretation into outright dishonesty.

Examples are numerous.

Suresh Naidu, economics professor at Columbia University, notes that capitalism is about reinvestment of profits into expansion. But the entire discussion of the 19th Century United States, is about the alleged advantage that slavery gave Southern plantation owners over northern family farmers.

No explanation of how the slave-free Northwest Territories were settled at the same time as the old southwest of Alabama and Mississippi, nor of why slavery died out in the North. No explanation that reinvestment in industry is geometric because it multiplies productivity, while slave reinvestment only adds arithmetically.

Nor does the film explore the steamboat, the telegraph or the massive railroad expansion. No discussion that a slave economy is barely capitalism at all, because it doesn’t involve free labor.

RELATED: ‘We the Economy’ Cheers Government Run Health Care

This can’t be the sum-total of Naidu’s understanding of 19th Century US economic development, but it’s how the film presents it.

Too often, the experts’ views are presented fairly, but uncritically. Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz is given room for his thesis that all of the productivity gains of the last 30 years have gone to the top 10 percent, but he uses household income and then fails to account for changes in household size.

Kate Williams of Reading University in the UK correctly links inflation and poverty to the rise of Hitler and racist nationalism in Germany. She ignores the parallel rise of the German Communists. The two political gangs, representing the great twin evils of the 20th Century, fought pitched battles in the streets of Germany, but only one is discussed.

Worse, Williams weirdly links post-WWII growth of the American suburbs to restrictions on wealth and capital, including rent control and land use, when in fact people had begun to flee the cities for the suburbs even in the 1930s.

Broadly speaking, the movie gets the Depression and the stagflation of the ‘70s correct. Even then, though, errors abound.

“Well, it’s difficult to say. But certainly the U.S. is probably doing the worst.” – Thomas Piketty to @NYMag when asked to rank several country’s economic response to COVID-19. https://t.co/6QBKV55D5A

— Capital in the Twenty-First Century (@Capital21stCent) April 28, 2020

Journalist Rana Foroohar says that in this time, “…people are going down, and Wall Street is going up.” People were definitely feeling squeezed, but adjusted for inflation, the Dow Jones Industrial Average declined by 45 percent between January 1970 and December 1979.

Likewise, Piketty caricatures President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher as craving the return of late 1800s Gilded Age capitalism.

Amazingly, the film correctly diagnoses the dangerous boom in easy credit from the late ‘80s through 2008, yet completely misses the massive foreign direct investment the Internet boom (and bubble) of the late 90s, possibly because they believe the root cause of the boom more government investment in creating the backbone than private innovation in learning how to use it.

A word about the film’s use of classic movie footage is in order.

It shouldn’t present early 20th Century film adaptations of mid-19th Century historical novels about late 18th Century events as actual documentary evidence of the conditions in the late 1700s. Perhaps using “We’re In the Money” to illustrate the Roaring ‘20s, when the song itself is used aspirationally in the Depression-era “Gold Diggers of 1933,” is intended as wry joke, but most audience members won’t get it.

Unfortunately, it’s not until 80 minutes in that we finally get to contemporary worries.

- Globalization has moved jobs overseas.

- New technology has placed a premium on brain power as opposed to physical power.

- China’s state capitalism is a return of the marriage of wealth to power, threatening the world.

- Off-shoring profits has separated companies from their communities.Internet companies do create fewer jobs than industrial companies.

- Technology companies do capture almost all the productivity gains.

- Real estate costs have created a wealth trap for millennials.

Conservatives, libertarians, and centrist economists and social scientists have noticed the same problems and dangerous trends for years. Joel Kotkin of Chapman University, who describes himself as a Truman Democrat, has documented California’s evolution towards neo-feudalism for years.

Libertarian Charles Murray has written incisively on the social separation that comes with increasing, permanent inequality.

Even Ed Conard, former managing director at Bain Capital, who wrote a book in response to Piketty, wants to get unproductive capital off the sidelines and into the game. Arthur Brooks formerly of the American Enterprise Institute has written extensively and eloquently about the dignity of work and earned wealth.

But the complaints are so rushed that Piketty’s preferred solution – massive taxation of wealth, with an ill-defined means of redistribution – fails to persuade because it’s unchallenged and alternatives are unexplored.

The movie had the opportunity, like Piketty’s book, to open a serious discussion about the social effects these authors have been talking about.

Unfortunately, it forfeited that chance when it opted for polemic instead of dialectic.

Joshua Sharf is a Senior Fellow for the free-market Independence Institute, focusing on public pension and public finance issues. By day a web developer, he has also found time to run for the state legislature, be a state editor for WatchdogWire, write for the Haym Salomon Center, and produce a local talk radio show. He has a Bachelors in Physics from U.Va., and a Masters in Finance from the University of Denver, and lives in Denver with his wife, Susie and their son, David. His work also appears frequently in Complete Colorado and American Greatness.