Why David Bowie Made Movies Better

David Bowie’s film work may seem to be an afterthought in comparison to his career as … well, is the term “rock god” too much or an understatement?

Actually, Bowie’s extraordinary, evolving work as a musician created a direct pathway from concert halls to the silver screen.

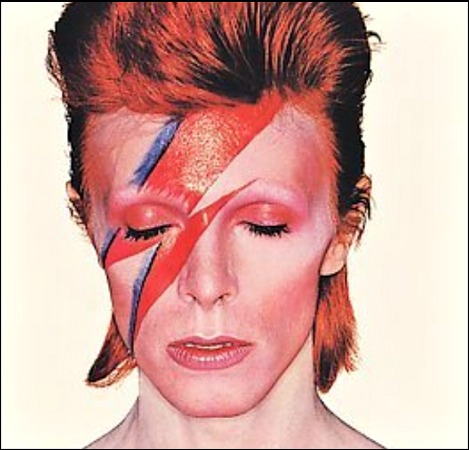

Bowie’s conceptual albums, performance art as Ziggy Stardust and “role” (or is it reputation) as a rock star from Mars laid the foundation for his abilities as an embodiment of our fantasies. His dreamy pop music was delivered in a hip, ahead-of-its-time manner It suggested Bowie was orchestrating the expansion of music art, but he was also self aware of how performance and fictional pop personas could be synergistic.

Call it rock kabuki or thespian pop, Bowie’s Stardust made him both a groundbreaking icon and something of a mystery. If he wasn’t really a rock star from Mars, then who the heck was he?

Cinema provided the singer with many masks, all of them different and tantalizing. Among the many faces he would adapt as his own was the title role in Roeg’s “The Man Who Fell to Earth.”

The character’s suave and strange demeanor, attired in Bowie’s ahead-of-his-time blend of androgyny and unceasing cool, made Roeg’s extraterrestrial a fascinating figure. The film, both overwrought and utterly intriguing, marked Bowie’s film debut.

He also played the title role of his subsequent film, “Just a Gigolo,” which co-starred Kim Novak and Marlene Dietrich in her final performance.The film itself remains impossible to come by).

The year 1983 marked two essential works in Bowie’s filmography: “The Hunger,” Scott’s trendsetting vampire thriller and Nagisa Oshima’s unforgettable “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence.”

In the former, Bowie’s outward style is matched by a tragic soul whose penultimate scene is a tour de force blend of performance and make-up effects. In the latter, he portrays a British soldier in a Japanese POW camp and, as in “The Hunger,” gives a moving performance and makes a stunning exit.

In his delightful “Into the Night,” director Landis cast him as a Peter Lorre-like villain, complete with memorable lip smacking and hissing. Julian Temple’s “Absolute Beginners” is best remembered for its astonishing opening tracking shot. Yet Bowie’s appearance and title song are the real highlights.

Aside from Bowie’s acclaimed and surprising 1980-81 detour to Broadway, where he portrayed John Merrick in “The Elephant Man,” his most surprising acting work came between 1986-1996.

The teaming of Bowie with Henson and George Lucas for the puppet fantasy “Labyrinth” engraved the cult of Bowie even deeper. His Goblin King terrorized and tantalized a teenage Jennifer Connelly to grand effect.

As the fantasyland equivalent of Ziggy Stardust, Bowie’s Jareth is alluring and eerie. Connelly seems both frightened and aroused by him. It’s arguably Bowie’s most well-known film role, and he’s wonderful in it. He’s a dark presence among a menagerie of creatures. Somehow the odd pairing with the cuddly Henson and mythmaker Lucas makes sense.

Most don’t recall that Bowie is in Scorsese’s massively controversial “The Last Temptation of Christ.” He plays, of all people, Pontius Pilate. What should come across like stunt casting instead reveals him to be a sharp character actor. His one scene with Willem Dafoe’s Jesus is understated and fascinating.

FAST FACT: David Bowie was born David Jones, but he changed his name to differentiate himself from Monkee Davy Jones.

It seemed only a matter of time before he teamed up with artist-turned-filmmaker Lynch. Both were button pushers who challenged and expanded surrealism in pop culture. Bowie’s brief, not entirely coherent appearance in Lynch’s “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me” is deeply unsettling. It seems to pay homage to Bowie’s music origins as a “space man.”

Bowie’s finest performance is in artist-turned-director Julian Schnabel’s “Basquiet,” in which Bowie portrayed Andy Warhol. Wearing Warhol’s actual glasses, gently conveying his speaking voice and summoning his inscrutable allure, Bowie taps into his own mysterious, seductive nature and gives us a portrait of an artist that feels intimate.

Many subsequent film roles had Bowie playing a (just barely) exaggerated, uber-cool version of “himself.” Think “Zoolander,” “Bandslam” and the TV series “Extras.” His last great film performance came as Nikola Tesla in Nolan’s “The Prestige.” Once again, Bowie was perfectly fused (pun intended) with a real man. Bowie’s performance suggests a complex figure, buried in his own mythmaking. Bowie’s literally electric introduction is as perfect an entrance as he’s ever given, whether on the big screen or on stage.

Rock stars don’t typically make great actors. They’re too self aware, too precious, too protective of their stage personas to become someone else. Bowie found screen roles that pushed his Ziggy Strdust concept further, then delved into characters both painfully vulnerable and disturbingly untouchable.

Transformation was a constant quality of Bowie’s art and his film work is a testament to an actor who took fine chances to make great art. There will never be another David Bowie.