Blame an entertainment culture that applauds black victimization, witness the hosannas thrown toward Beyonce and Kendrick Lamar in recent days.

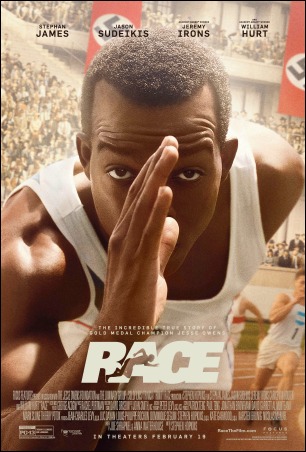

“Race” acknowledges the hate Jesse Owens faced both by Adolf Hitler’s minions and his own countrymen during the 1936 Olympics. Owens didn’t buckle. He inspired. “Race” does the same, even if the film doesn’t dig deep beyond the considerable legend.

It starts in Cleveland in 1933. Young Jesse Owens (Stephan James in a fine, unfussy performance) can barely look his new Ohio State track coach in the eye.

Jason Sudeikis, successfully cast against his comic type, tells Jesse that’s simply bad manners. Social graces count to the budding superstar. Owens was raised right, and he’ll need every ounce of grace to endure what looms ahead.

He’s arguably the fastest man alive. But with great power comes great responsibility … as well as historical gravitas. Owens is a cinch to make the U.S. Olympics team to be held in Germany. Should Owens, or any American athlete, take part in games thrown by the Nazi regime?

Once again, a proud, talented black man must endure the hate of the era to teach us all a lesson. We saw similar themes echo throughout “42,” 2013’s fine Jackie Robinson biopic. Then, as well as with “Race,” the basic beats are true.

That takes nothing away from the real men who proved heroic without a cape or special powers. Although Owens really could fly around a track.

RELATED: Does Clooney Have a Diversity Problem?

Owens’ story is so much larger than life it begs for some clarity, something new or subtle to add context. We don’t get enough of that in “Race.”

Instead, it’s the same reliance on reaction shots from all the usual suspects — the crowd, the coach, the family the defeated parties and, in this case, Hitler.

Owens deserves our respect above and beyond his track skills.

“I always pay my way,” Owens tells his family, a clan with a complicated patriarch who demands more screen time than permitted.

The father (Andrew Moodie) carries the burden of the black men of his era. He’s not old but tired, a run-down figure who even moves like a man expecting something bad to happen simply for being alive.

His son’s grace on the field lets him push past some, but certainly not all, the era’s racism.

“The American people need a hero,” says Jeremy Iron’s character, arguing Owens should participate in the upcoming Games. William Hurt, given precious little to do, argues such an appearance would indirectly give approval for Germany’s barbarism.

That battle, like much of “Race,” isn’t as fully developed as needed.

‘Race’ Then … and Now

Sudeikis’s coach is as progressive as the era will allow. Some of the film’s dialogue also feels unerringly 21st century. Phrases like “in their house” and “be more inclusive” sound more like current chatter than what was spoken during the 1930s. The film’s callback dialogue is similarly precious. That takes us out of an era so painstakingly recreated by the film’s costume and set design squads.

Director Stephen Hopkins (“The Reaping,” “The Ghost and the Darkness”) conveys the majesty of the main event. It’s glorious to watch Owens streak across the screen, bringing the races together with every stride.

Owens is a good man, but he’s not deified here . He refuses to shake an opponent’s hand in one scene. His weakness for golddiggers dings his image.

“Race” is far from perfect, too. It still inspires us a time when many pop culture institutions seem eager to tear us apart.