Why Silent Film Is Equal to Sound Movies

Silent film is art. At its best – which is as good as any art – silent film awakens and stirs people intellectually and emotionally.

Director D.W. Griffith supposedly said to his great actress Lillian Gish, “Above all, I’m trying to make you SEE.” And that’s what good silent film does.

King Vidor’s “The Big Parade” makes you SEE and feel how lives become entangled and wasted by war, how misguided enthusiasm leads people into the horrors of war and how war can tear apart and rearrange love and connection among people.

The sad, searching images of Dmitri Kirsanov’s “Menilmontant” bring you inside the experience of abandonment and loneliness. No other work of art (or poem, novel or painting) takes you there more deeply or fully. The vast emotional range of Chaplin’s “City Lights” (or “The Gold Rush”) encompasses most human experience.

Silent film isn’t less than film with talk, any more than black and white film is less than film in color. It’s just different. The very absence of talk or color demands that a film take place within the viewer more than if the film has talk and color. Those absences give silent film a unique poetic, musical dreaminess.

Many people now claim that realism is the thing (“Star Wars?”). Chaplin and Sergei Eisenstein, among other filmmakers in the silent period, did not value realism as we do. They knew that sync sound meant talking and therefore a level of realism that they considered inimical to the poetry and musicality of cinema.

FAST FACT: Charlie Chaplin supported himself by making toys, polishing shoes and performing with clog dancers before embarking on his iconic screen career.

Eisenstein wrote that the only artistically legitimate use of sound would be contrapuntal to the visual image. Chaplin didn’t use speech in a movie until 1940, 13 years after “The Jazz Singer,” the first commercial picture with synchronized sound.

Actress Mary Pickford said that it would have made more sense if the movies had started with sound and then discovered silence.

So silent film is not a compromise. It’s not old-timey cuteness.

When people think that silent film is jerky and silly-looking, it’s because they’ve seen it mis-projected. Film in the silent period usually ran at slower speeds (12 to 24 frames per second) than the speed determined for talking pictures (24fps). And after a few years, projectors with speed controls largely disappeared, or were ignored.

So silent film was projected too fast. Chaplin and Keaton didn’t twitch around They are graceful and elegant in their movements.

Recent digital restorations have corrected the speed problem. Now, silent film looks the way it should. Those bad memories persist.

The Denver Silent Film Festival, which I direct, shows silent film the way it should be shown. We never present films as exercises in nostalgia. We don’t go for “old-timeiness,” either. We show work we believe is good, by any measure.

We also don’t show silent film in silence because silent film was never shown silent. From New York to Paris to Moscow to Julesberg, Colo., silent film came with live musical accompaniment. It could be a full orchestra playing a score written for a film. Or, it might be the local piano teacher improvising in the dark – there would be music.

For our festival, we have music performed by musicians with international reputations.

I’ve never heard someone complain that Picasso’s “The Old Guitarist” is an “old” painting or that Jane Austen’s “Emma” is an old book. The movie industry proclaims that new is the only thing that matters. That’s just industry hype. It’s how they make their money.

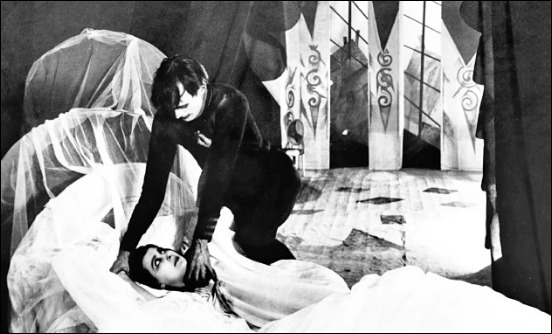

We don’t have to care what they say. “The Crowd” shows economic dislocation and personal impotence as well as anything made in the last year. “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” – seen on a full-sized movie screen and not a computer – is as disturbing as “Saw,” “Scream” or “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.” And “A Trip to the Moon,” made by Georges Méliès in 1902, is as entrancing as “Gravity,” as playful as “The Martian.”

But silent film as a body of work is not better than sound film. It’s simply its equal.

—-

Howie Movshovitz is a veteran film critic and director of the Denver Silent Film Festival. He serves as Director of Film Education in the College of Arts & Media of the University of Colorado Denver and helped found the Starz Film Center.

THE DENVER SILENT FILM FESTIVAL 2016

April 29-May 1

The Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, Littleton, Colo.

FRIDAY:

“Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ” (Fred Niblo and Charles Brabin, 1925, 143 minutes): “Ben-Hur” is a genuine film epic, with big sets, literally hundreds of extras, horses and Roman soldiers, plus the justly-famous chariot race (also filmed magnificently by William Wyler in 1959). The film is also an exuberant melodrama, marked by innocence, great injustice, high passions – and, of course ending with the Crucifixion. Accompanied by The Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra.

SATURDAY:

10:30 a.m. – A conversation with David Shepard, the 2016 recipient of The Denver Silent Film Festival Career Achievement Award.

12:30 – “Peter Pan” (Herbert Brenon, 105 minutes): This film is so light and evocative that it makes you believe the only way to film Peter Pan would be silent and in black and white. The story needs the poetry of silent film to reach the exquisite fantasy that author J.M. Barrie imagined. The film is endlessly ambiguous with its conflicting hints of romance and the need for mothers, its love of unrestrained youth and the demand that we grow up. With Mary Brian as Wendy, the great movie villain Ernest Torrence as Captain Hook (see “Tol’able David”), Virginia Brown Faire as Tinker and Betty Bronson as Peter. You will believe. Accompanied by Rodney Sauer

3:30 p.m. – “The Unholy Three” (Tod Browning with Lon Chaney, 1925, 86 minutes): Superficially, “The Unholy Three” is a film about a jewel heist – a description that gets nowhere near what the film actually is and does. The trio of the title consists of Victor McLaglen as a carnival strongman, Harry Earles playing a midget disguised as a baby and Lon Chaney mostly disguised as an old woman. The sight of the three of them is unnerving, as is the film. Also with Mae Busch, an accomplice of sorts, but still a normal human being – just for contrast. Accompanied by The UCD/DU Student Orchestra led by Donald Sosin.

6 p.m. – A program of short comedies: “His Wooden Wedding” (Hal Roach/Charlie Chase, 1923, 20 minutes), “Bacon Grabbers” (Hal Roach/Laurel and Hardy, 1929, 20 minutes) and “A special Buster Keaton Treat.” Accompanied by Rodney Sauer

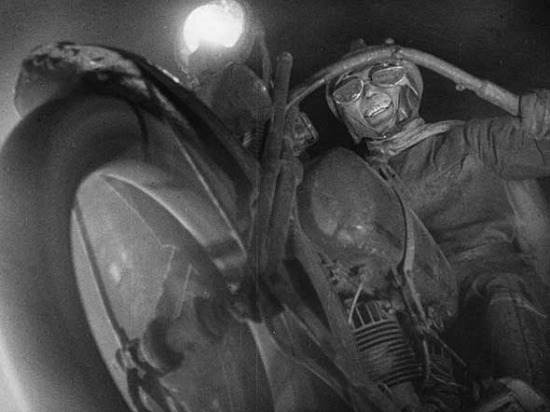

8 p.m. – “Spies/Spione” (Fritz Lang, 1928, 90 minutes): Fritz Lang is one of the greatest filmmakers, yet he’s slowly being forgotten. He’s a director of intense focus. In “Spione,” just about everyone is a spy, so the film takes place in a world that’s entirely perverted by deceit, betrayal and struggle for power, and because the various organizations have no concrete identity, events can feel utterly out of control. Rudolf Klein-Rogge plays the arch-villain. Note his hairdo. Accompanied by Hank Troy.

SUNDAY

11 a.m. – “The Blot” (Lois Weber, 1921, 80 minutes) and “A House Divided” (Alice Guy, 1913, 13 minutes): Lois Weber, once one of the most highly regarded directors in America, took on tough subjects like poverty, birth control and – most of all – the lives of women. Unlike male filmmakers, Weber places action where her women characters spend their lives. She shows her characters on back porches, and in kitchens, parlors and food markets. In “The Blot,” the daughter of an impoverished college professor (Claire Windsor) is courted by a callow rich student (Louis Calhern). She tells him to come back when he becomes a better person. Alice Guy, the maker of “A House Divided,” began her career in France, and is the first director of any gender to be credited on screen.

Accompanied by Hank Troy.

1:30 p.m. – Panel discussion: The eccentric brilliance of silent comedy: Panelists: Jim Fiumara, Walter Chaw and Sarah Hagelin

3:30 p.m. – “Tol’able David” (Henry King, 1921, 90 minutes): In this rural fantasy, David (Richard Barthlemess) is no longer a boy but not yet an adult – he’s just “tol’able.” At the same time, he will be called upon to save the family and the farm from an evil gang. The great silent film villain, Ernest Torrence, plays the evilest of the evil ones. Accompanied by Hank Troy.

6 p.m. – New silent films by students in the College of Arts & Media at the University of Colorado Denver

8 p.m. – “The Phantom of the Opera” (Rupert Julian, 1925): This is the original of the now-famous story of perverse, obsessional love deep within the Paris opera. It features Lon Chaney in perhaps his most famous role. The designers of the flamboyant stage production looked to the work of the film’s great art director Ben Carré. The film will be shown in 35mm with its magnificent two-strip Technicolor sequence of the masked ball. Accompanied by Donald Sosin